“Work and play are words used to describe the same thing under differing conditions.”

This quote’s attributed to Samuel Langhorne Clemens (aka Mark Twain), and, you could argue, one goal of gamification. When you love something, when it’s your passion, it doesn’t feel like work.

But then, this one is also true:

“When you play, play hard; when you work, don’t play at all.”

-Theodore Roosevelt, 26th President of the United States

And also this one:

“All work and no play doesn’t just make Jill and Jack dull, it kills the potential of discovery, mastery, and openness to change and flexibility and it hinders innovation and invention.”

-Joline Godfrey, former Polaroid executive and CEO of The Unexpected Table

There’s wisdom in all three, and they’re not mutually exclusive. But these different takes can all be applied to gamification: as a practice it can be exciting, lame, the way to shake up work, and also a contentious, hot mess.

With impacts that are highly difficult to quantify, gamification ranges from generating more stickiness in your products and motivation for people completing routine tasks over and over, to doing the exact opposite: turning people away, wearing them out, making them frustrated, or even angry.

In this week’s The PTP Report, we look at gamification: how (and why) gaming and its mechanics (like leveling up, badges, points, winning, new tiers, unlockable content, avatar customization) are becoming ubiquitous, ways it works across industries (and sometimes fails miserably), and consider gamification with AI, which may soon impact the future of work.

Why Are We Gamifying Everything, Anyway?

In his article for the MIT Technology Review, Bryan Gardiner pins the origins of our current obsession with gamification on a 2010 TED talk by game designer Jane McGonigal, called “Gaming Can Make a Better World.”

In looking at the current status of the practice, he’s not too enamored with the results.

The goal is utterly reasonable: games are more popular than ever, while work engagement is at an all-time low (by current measurements, anyway). People happily pour unpaid hours into doing virtual work, like raising crops, tending pets, building and organizing structures; they create virtual people and work (for fun) to get them money and outfits, gear, boosted abilities, virtual objects, and attention.

Like the Mark Twain quote, gamification could theoretically shift the conditions that can make some work feel unpalatable, with the aim of moving the less-than-thrilling tasks more in line with a flow-state giddiness we associate with play.

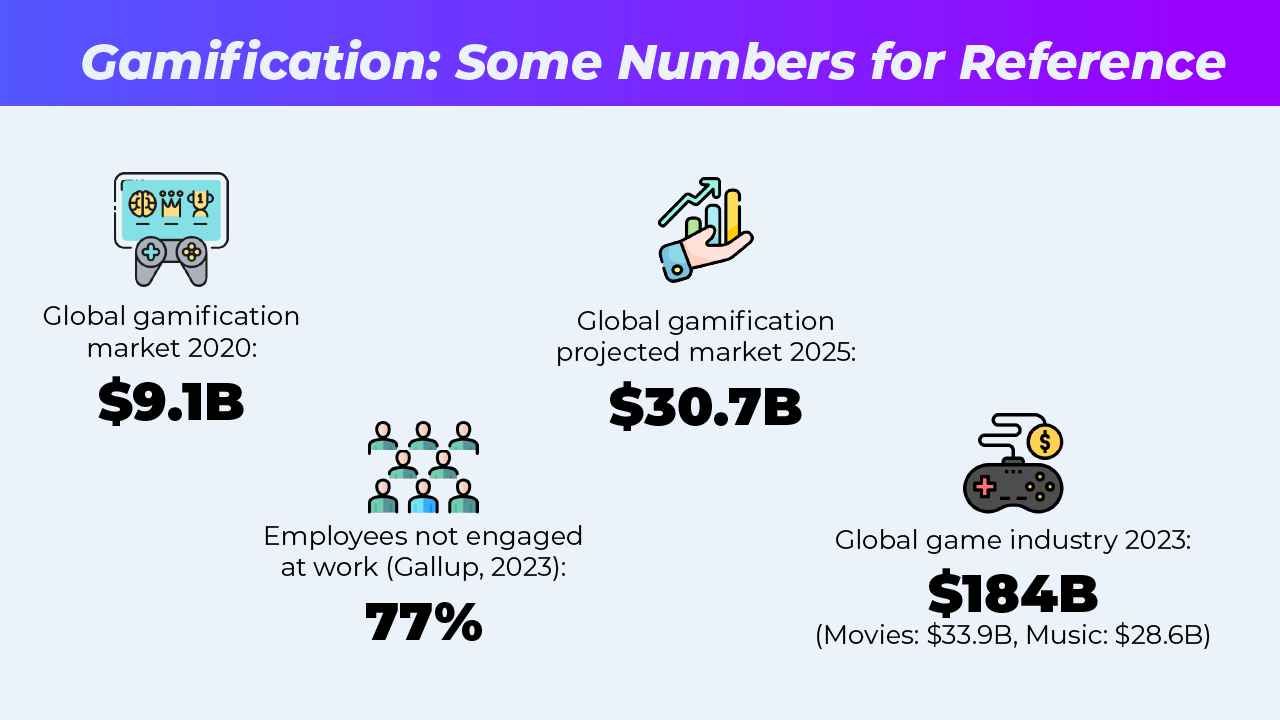

And while the impact of gamification can be difficult to nail down, the dollars being invested cannot be denied.

So what does this look like, practically?

Current Examples

If you had kids during the Covid lockdowns, you probably got a crash course in educational games, and that trend has only continued since, with the games below being a steady part of my own kids’ ongoing education:

- Gimkit: Individual or in teams, virtual money gained and spent through activities and quizzes

- Kahoot!: Variety of games, can create avatar, unlock accessories through questions

- Blooket: Blooks represent players in a variety of games with integrated questions from teachers

- Pear Deck: Interactive flashcards and more

- Prodigy: RPG with integrated questions (ELA and math), moving the action along

You could argue that educational games are different than gamification in education, since the latter refers to bringing gaming concepts to non-game contexts.

From this POV, social media as it’s built today, with gamified mechanics such as likes (loves, thumbs ups, numbers of followers, and more) translating to a game’s points, or levels, and lean interfaces rife with icons and busyness, and interactions like swiping akin to game actions, is wholly game-fied to its core. If you scroll you’re likely to be met with something unexpected, another reward associated with game exploration.

A highly successful example of gamification in business, is the mapping app Waze, which actually began life as a game (users aimed to be the first to drive through virtual pallets by going on a certain route), before becoming a wildly popular crowdsharing traffic app.

Waze was a 100-employee company when Google acquired it in 2013 for $1.3 billion, famous for amassing quality, real-time traffic data from its users for free.

One secret to Waze’s success (and dedicated community) came from using game aspects like avatars, points (taken from likes), and levels that reward spotting things while driving. User get achievements, and can view their overall rank, very like the educational games described above.

Successes like Waze have seen superficial game aspects—avatars, competition, badges, levels, and points—be so broadly applied across industries that consumers often barely even notice them anymore.

What’s Working (and Not So Much)

Just like games themselves, gamified interfaces can hit a “sweet spot,” where they are inherently pleasurable to interact with (colorful, fluid, responsive, stylish). This pleasure inspires interaction, by being like play itself.

When this is coupled with a potential for immediate feedback via competition, demonstrated progress, and rewards, the experience is far more likely to encourage, and motivate use.

Add in giving people the unexpected, such as by inobtrusive exploration, and gamification can bring genuine enjoyment and motivation to tasks that someone needs to do anyway, such as required training.

(Compare such a training system to the more traditional method: sitting through hours of video with taking quizzes given afterwards, and it’s easy to see the appeal.)

Personalization is another key to successful gamification. In Waze, the ability to tailor your experience with an avatar and variety of voice options brings more enjoyment to using the app alongside others.

Inversely, gamified interfaces do often frustrate users, by adding superficial weight on top of tasks without the play-like experience.

If an interface is not enjoyable (such as by flickering, lacking sufficient responsiveness, not rewarding exploration, or being cumbersome), and added points, badges, bells and whistles just serve as distractions over an unchanged core, it can feel like a pointless assault on one’s senses and only increase stress and sensory overload.

Distinctly linear progression, for example (such as clicking through slides in a set order, regardless of how you interaction), gamification can begin to feel manipulative and cynical.

When the experience of play is lacking, gamification results in wasted time for no benefit, bringing uninspired mechanisms of play (back to that Teddy Roosevelt quote) which users just ignore. Offering workplaces no benefit.

As game designer and former USC educator Jeff Watson said: “A game is about play and disruption and creativity and ambiguity and surprise.”

But this kind of gamification he characterized as being: “…about ‘checking in,’ being tracked … [and] becoming more regimented. It’s a surveillance and discipline system—a wolf in sheep’s clothing. Beware its lure.”

The key to success, aside from great UI, starts with understanding the user and situation, ensuring that the total experience enhances, instead of encumbers, the end goal.

Successful gamification brings genuine engagement, rather than simply dangling a digital carrot in a user’s face, where they are forced to keep clicking regardless.

AI and the Future of Gamification

Artificial intelligence and gaming are inherently linked: as considered by Mike Pearl for Mashable in his piece: How gamification sparked the AI era in tech. As far back as 2013, Super Mario Brothers was being used as a benchmark for testing AIs.

While this includes beating human champions at games like chess and go (as Google DeepMind’s AlphaGo did in 2016), open-world gaming has been a critical method for teaching AIs to behave more like people, across a whole spectrum of games (like: Jeopardy, Frogger, Q*Bert, Dota, No Man’s Sky, Grand Theft Auto, etc.)

Minecraft is one example heavily used by AI developers, as in this example by OpenAI. Video training with Minecraft enabled AI models in 2022 to harvest materials and craft implements in-game, as well as search, hunt, swim, and eat food.

Today, users often experience sensations of play in our interactions with chatbots: prompting is often like exploring, with unpredictable results that often fail to meet our goal. But there is no clear progression, and potentially not a lot of joy, depending on your goals.

AI is certain to transform gamification in a big way, just as AI-powered game mechanics are already at work transforming that industry.

(Check out surging startup InWorld’s website for a peek at the future of AI in gaming, where you can try chatting with one of their fictional characters.)

With AI in gaming, you can already see game characters speaking their own, variable dialogue, and from this it’s easy to imagine applications in training, for example, being wholly revolutionized.

Imagine employees able to navigate virtual workplace scenarios, as avatars, interacting with fictional co-workers directly, experiencing workplace events (including edge cases, training scenarios, and the worst-case) that allow them to learn by doing.

AI also excels at personalization, one of the cornerstones of successful gamification, as well as generating unexpected situations, with direct feedback on the fly.

Conclusion

Whether you believe work and play should overlap or not, there can no doubt about three things: workplace engagement is down, gaming (as an industry) is surging, and investments in gamification, perhaps the intended intersection, continue to rise.

The prospect of harnessing the joy of play and playful exploration, arousing in people the same creativity and passion we see in their gaming, is extremely powerful, even after a decade of mixed results.

AI is already transforming the way we work, and with a history inseparable from gaming, AI in gamification will soon change the way people learn, shop, and work.

References

How Gamification Can Boost Employee Engagement, Harvard Business Review

Why AI playing video games is a big deal, Freethink

Podcast: How games teach AI to learn for itself, MIT Technology Review

Gamification Is Everywhere: Why Companies Can’t Ignore It, Forbes